Wild Herbs in Homeopathy by Roz Pollock

In the UK these last few years I’ve become more aware of something that feels like a revolution; increasing interest in holistic health areas such as homeopathy and herbal medicine. It seems like a growing number of people are now interested in more natural products both to reduce toxic exposure to themselves and to the environment. Inspiration for this movement can begin with a desire to live more sustainably, a desire that can then develop into living regeneratively and finding ways to support and enhance nature around us, whilst boosting our own health and happiness. However, despite this recent growth in herbal interests, conventional medicine remains the dominant healthcare choice in the UK.

One way to live more holistically is by using more locally grown and processed plants. If you can grow or collect these yourself than all the better in terms of ensuring provenance whilst promoting personal empowerment. Back in 2019 a survey was published by a self-funded researcher on the use herbs for health. Amongst the responders it was those aged 36-55 where this proved particularly popular with 65% (n=74) believing herbal remedies are effective. Responders also appreciated fewer side effects and having the choice of additional treatment options. This was especially the case for more minor complaints such as sleep or anxiety where conventional medicine has little to offer. Around a third of responders also grew their own herbs such as mint, rosemary and lemon balm for health benefits1.

Slightly further back in 2004 another survey, this time from Kew, commented that whilst Britain is one of the world’s major importers of herbs there is relatively little interest in the health benefits of our own wild plants that often literally grow on our own door steps. Instead the majority of the tinctures, creams or infusions we use come from imported or cultivated plants2. So even when herbs are used, they often originate from another country and are subject to transportation or have been grown locally in a controlled climate which uses additional resources. As a nation of garden lovers we currently and historically seem to prefer the more exotic and cultivated plants with local plants often labelled as mere weeds, but why is this?

A friend from Lithuania once commented that in Eastern Europe herbal pharmacies were much more common and she was surprised when she first came to the UK to see very few such pharmacies. She wondered if this was related to wealth of the UK on the back of the industrial revolution that took

place in the later 1700s and early 1800s, and that here we were happy to invest

this extra wealth into more expensive allopathic healthcare? Looking back further to the 1600s and earlier in Great Britain, it seems locally grown herbs were much more commonly used and considered key ingredients for everyday life activities such as eating, medicines and pest control. So there appears to have been a cultural shift around this time. During this period a lot was happening. On one hand there was much religious division with ongoing clashes on the back of the Reformation. Over a similar period there was also the Little Ice Age that gripped Europe between approximately the 1500s and 1800s. As a consequence the climate deteriorated with longer periods of rain and colder temperatures. Growing conditions were generally difficult with an increased risk of crop failure and subsequent famine, distress, poor public health and further division. These times are portrayed as very tense. People were often scared and desperate which perhaps explains somewhat why the Witch Trials also happened throughout Europe, particularly in Germany, France, Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands where the greatest number of prosecutions are said to have occurred. From 1590 in Scotland and particularly around 1650, it is estimated that 2,500 of those accused of witchcraft were convicted, tortured and executed3. These trials continued right up until the early 1700s. Those accused were often social outliers, those who existed on the fringes. Mostly women (>80%), those who used herbs and worked as healers were particular targets, especially if a patient being treated subsequently died. This was a very dark time of superstitions with accusations from enemies, neighbours, former friends and even family members. I’ve often heard it speculated that the use of local herbs by the general population fell out of practice in part for fear of being accused of witchcraft and that the essence of this fear still lingers. Indeed, there are limited written accounts of how herbs were used and the knowledge past down by word of mouth also seems limited. In Eastern Europe witch trials also took place but these were fewer and later, perhaps another reason why herbal traditions are better preserved there? Back to the UK and the industrial revolution, another factor to consider is the mass migration of people from the countryside to cities where living conditions were cramped and working hours long. Both the time and the green space to grow and find herbs was considerably reduced as the population generally became more urbanised and disconnected from nature. So when the biomedical era began in America in the early 1900s presenting pre-packaged pills and bottles as medicine, it was only a matter of decades before this system was also embraced in the UK as mainstream medicine.

In the meantime over 200 years after the witch trials in Scotland the word ‘witch’ is still typically accompanied by the image of an old haggard woman with warts, cats, a cauldron and all sorts of wicked spells. To call someone a witch was most often an insult. However in the 90s an author by the name of JK Rowling sat in an Edinburgh coffee shop and began to write a children’s series of books about a boy named Harry Potter4. First released in 1997, this series proved extremely popular and on the back of this, witchcraft was re-branded positively, initially amongst children but this influence soon spread. In more recent years I’ve also been noticing another ongoing shifting trend in the popularity of our local plants. In 2025 Mo Wilde, a Herbalist, Ethnobotanist, Forager and Researcher based in Scotland went on a book tour to promote her latest book “Free Food. Wild Plants and How to Eat Them (2025)5. With bulging audiences and a 4-star review from the Telegraph where her book was described as ‘fascinating’ interest in this area is now evident. This follows the success of her previous book “The Wilderness Cure (2022)6 and The Microbiome Project (2023) where Mo and 23 of her foraging friends only ate foraged food for one or three months. The participants of this preliminary study experienced health benefits including an increase in beneficial gut bacteria, improved body weight and even a reversal of pre-diabetic status7. The Microbiome Project 2 (2025) in now in the pipeline to explore this area further8. Perhaps their foraged diets are much more similar to what our British ancestors were eating prior to the 1600s?

However, let us not forget that plants can be poisonous. If in doubt of this, a trip to the Poison Garden in Alnwick Castle Garden will soon open your eyes. A lot of non-foragers I chat too speak of their fear of picking the wrong plant and this is a valid fear. Those who take part in the Microbiome Projects are experienced foragers. However, as Mo Wilde likes to tell her audiences “if you can tell the difference between a lettuce and a cabbage this is a great starting point”.

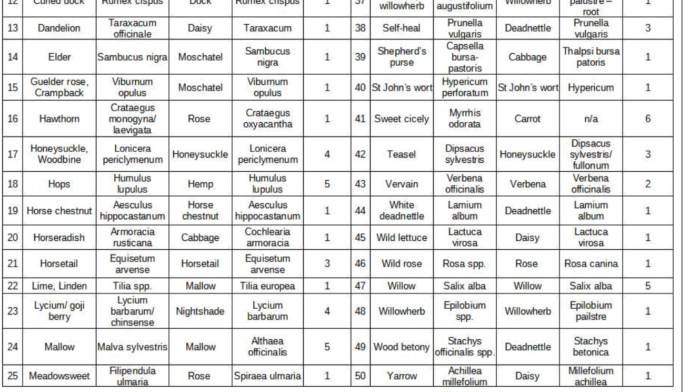

How is all this relevant to homeopathy? Another classic foraging book based on locally available plants is Hedgerow Medicine, first published in 2008. The focus here is the herbal properties of these plants, as described by herbalist Julie Bruton-Seal and her husband Matthew Seal. This book was partly inspired in response to the findings of the Kew survey referenced above and covers 50 wild plants commonly found in the UK. It’s purpose is to promote the health benefits of these easy to identify and abundant plants and the health concerns addressed9. Initially I was curious about how many of these 50 wild plants (see Table 1) were also available as homeopathic remedies, having recognised one or two in the list. For this, a comparative reference was required and here I chose the very popular Materia Medica by Murphy (2020) that contains over 1,500 Homeopathic and Herbal remedies10.

Table 1 Comparison of Hedgerow Medicine Plants with Murphy’s Materia Medica and Helios remedy availability

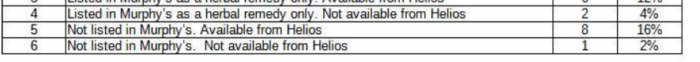

Table 2 Availability as a homeopathic remedy

Table 2 provides a summary of the foraged plant coverage in Murphy’s. Whilst 62% (n=31) of the 50 plants included in Hedgerow Medicine are described in Murphy’s as a homeopathic medicine, 94% (n= 47) are available as homeopathic remedies from Helios. Helios shine particularly bright here. A further detail worth highlighting is that whilst homeopathic names reflect the botanical names at the point the remedy was established, herbal names reflect the most recent botanical name, resulting in some differences. In this sample of plants 22% (n=11) have a different genus or species name due to this. Yarrow is a slight exception here; the genus and species name have been swapped around.

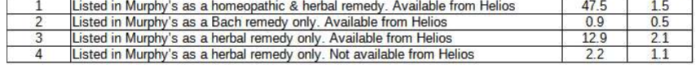

As summarised in Table 3 and as an approximate, of the foraged herbs listed as homeopathic remedies in this popular Materia Medica, those listed as homeopathic remedies have an average 1.5 pages of text for all these remedies. The most popular remedy here is of course Hypericum and unsurprisingly this has the most coverage at 3.7 pages of text.

In total only 3 (Hypericum, Rumex crispus and Thalpsi bursa patoris) of these foraged remedies have more than 3 pages of text. Of these, I have only thus far considered Hypericum as a homeopathic remedy to use. Further, as part of my homeopathy training, only Hypericum, Symphytum and Urtica were covered in considerable depth, a mere 6% of this sample. Overall, these statistics suggest lukewarm interest in these foraged homeopathic remedies. Taraxacum officinale had a little coverage in lectures but is not nearly so popular as other liver support remedies such as Chelidonium. Dandelion root is much more popular in herbal medicine.

Table 3 Number of pages of text per plant

So far, it looks like our local foraged plants are not generally the most popular as homeopathic remedies. If so there are several possible reasons for this. An aspect of homeopathy that is of particular interest to herbalists is the use of poisonous plants in remedies. Either such plants cannot be used for herbal medicines or a special licence is required and usage is restricted and closely monitored. One example is Digitalis (Foxglove). This is a cardiac tonic that was previously used for hundreds of years to stimulate the heart beat. The therapeutic dose is very close to the lethal dose and as such, requires very careful handling. It is however available as a homeopathic remedy with a particular affinity for the heart and no concerns of overdosing.

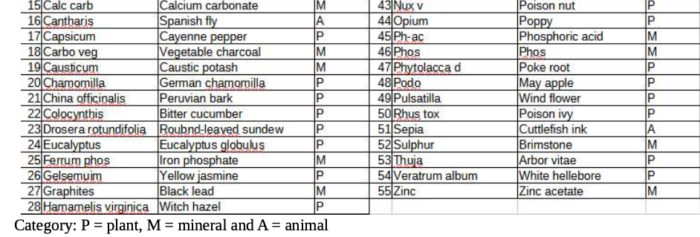

This highlights an important theme of homeopathic remedies and to illustrate this further I will refer to another example list, this time of popular homeopathic remedies as listed in Table 4 and originating from the Homeopathic Constitution 12.

Table 4

In Table 4 51% (n=28) of these popular homeopathic remedies originate from plants, 42% (n=23) from minerals and 7% (n=4) from animal materials. Of the plant remedies, 89% (n=25) are considered toxic to varying degrees and by my estimation, approximately 39% (n=11) of these plants could easily be found growing wild in the UK. As it turns out, it’s no coincidence that the majority of these popular homeopathic plant remedies are toxic; by their very nature poisons always produce symptoms and therefore an associated symptom profile in a homeopathic proving. As such they are much more reliable as a homeopathic remedy. When it comes to non-toxic herbs on the other hand, some produce a lot of symptoms in a proving whilst others produce very few11. The results from my initial comparison don’t seem very surprising any more and it’s of further interest that in both examples, about 10% of the plants used are non-toxic.

A further homeopathic advantage in relation to herbal remedies is that a little goes a very long way. Take Arnica montana for example, a plant that originates from the Alps. It grows wild in only a very small part of the UK as conditions are generally unfavourable. It is hugely popular as a first aid remedy in both homeopathy and herbal medicine. However given it’s scarcity, Arnica represents a wild plant that would benefit from preservation rather than ongoing cropping. Luckily it can be cultivated and this is how much Arnica is sourced nowadays. As a homeopathic remedy it is further preserved. A related remedy is Bellis perennis or Daisy, also from the Daisy family. In great contrast to Arnica, Bellis grow easily and abundantly in the UK. Whilst Bellis is on the radar of most homeopaths, it is not nearly so popular as Arnica and in Murphy’s, Bellis has a mere 2.75 pages of description compared to the 5.25 pages of Arnica10. The mental picture described is also much shorter, for which there are two main possibilities. One that the mental picture is indeed very limited. The second is that it has had comparatively little attention in provings. As a non-toxic plant, it is possible that an assumption was made that it would have limited homeopathic ability. However, maybe just maybe, there’s more to the humble daisy then meets the eye? As a herb it is also in the shadows, with some herbalists like Nikki Darrell speculating it may be one of the most over-looked herbs that grows so abundantly in the UK. Traditionally it was much more widely used and with this in mind, there could be more to see here. Further, optimal picking of the flowers stimulates further growth, an example of humans benefiting plant growth.

Finally, no homeopathy article would be complete without a nod to the great man himself and his Organon14. Amongst his many talents, Samuel Hahnemann was also a chemist. As such, it’s of no surprise that Chapter X of the Organon is dedicated to the Preparation of Medicines (Aphorism 264-271). Aphorism 264 states “The true medical-art practitioner must have the most genuine full strength medicines on hand in order to be able to rely on their curative power”. In this regard we’re in a very fortunate position in the UK with several excellent homeopathic chemists and a wide array of high quality remedies on hand. Whilst homeopathy remedies of local foraged plants appear less popular at this time, pharmacies such as Helios have an excellent selection to choose from. So perhaps the time is now to become better acquainted with these remedies for the benefit of our own health as well as that of the nature around us. There is of course the option to make our own remedies too. Also from the Organon “If the physician prepares his homeopathic medicines himself, as he should always do to rescue humanity from disease, he may use the fresh plant itself since only a little of the crude plant material is required” (Aphorism 271). With detailed instructions included on how to make various homeopathic potencies, a good starting point would be non-toxic herbs14.

As a result of this review, I can’t help but wonder if there are not more secrets to learn from the abundant plants and herbs that surround us. These plants live and adapt to the same environment that we live in and in many cases, continue to thrive. There is great wisdom in this, and also great hope.

References

1. Lazarou R., Heinrich M (2019). Herbal medicines: Who cares? The changing views on medicinal plants and their roles in British lifestyles. Phytother Res.; 33(9):2409-2420.

2. Kew Gardens (2004). Britain’s Wild Harvest: The Commercial Uses of Wild Plants and Fungi. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and The Countryside Agency, London. Preston, C.D.

3. https://witches.hca.ed.ac.uk/accused/A/EGD/918 accessed on 23rd June 2025.

4. JK Rowling (1997). Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. London: Bloomsbury.

5. Mo Wilde (2025). Free Food. Wild Plants and How to Eat Them. First ed. GB: Simon & Schuster.

6. Mo Wilde (2022). The Wilderness Cure. First ed. GB: Simon & Schuster.

7. https://monicawilde.com/the-wildbiome-project-results/ accessed on 23rd June 2025.

8. https://monicawilde.com/the-wildbiome-project/ accessed on 23rd June 2025.

9. Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal (2008). Hedgerow Medicine: Harvest and Make Your Own Herbal Remedies. Shropshire: Merlin Unwin Books.

10. Robin Murphy (2020). Nature’s Materia Medica. 4th ed. USA: Lotus Health Institute.

11. Matthew Wood (1997). The Book of Herbal Wisdom. USA: North Atlantic books.

12. https://homeopathicconstitution.com/homeopathic-remedies-common-polychrests/ accessed on 23rd June 2025.

14. Wenda Brewster O’Reilly (1996). Organon of the Medical Art by Dr. Samuel Hahnemann. Adapted from the 6th ed. USA: Birdcage Press.

Bibliography

Lessons from the Plant Medicine Apprenticeship https://theplantmedicineschool.squarespace.com/apprenticeship https://squaremilechurches.co.uk/resources/online-exhibition/themes/theme/herbs-heath-and-medicine/ https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zwkm97h/revision/3) https://www.thecollector.com/european-witch-hunting/ https://blog.historicenvironment.scot/2022/06/the-witchcraft-act-and-its-impact-in-scotland/ https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zrc6hcw#z4wy3j6 https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/zrc6hcw#z4wy3j6 https://prairiestarbotanicals.com/blogs/news/herbalist-and-witches-a-brief-history? srsltid=AfmBOoruVBlbxDcYK4kfOVv5cH2o58Vl2HjY3NSLSKKZneGYDI5-4O2p